Social media, email, retailers, service providers, insurance. For most people, the list of important online accounts is long. Here’s how to keep them safe — and regain control when you’re hacked.

Time and time again, there are reports of a new company that has suffered a computer breach where hackers have obtained user account information. Databases containing millions of login details are openly circulating on the internet and show the extent of the problem. It doesn’t matter how long your password is if the company doesn’t protect it.

Moreover, most people today have not just a few but tens or hundreds of accounts on different websites. Some may not be that important, but many are. Either by their nature, like email and social media, or because of what they contain and their sentimental value to you. Imagine you’ve spent 20,000 hours on an online role-playing game and suddenly hackers get in, change your password and email address and rename your character “Same password everywhere.” Bummer.

Hackers aren’t just looking for financial accounts, emails, and social media. They also hunt accounts in various digital stores, with Steam accounts with many games being particularly sought after, and some like to lock victims out of forums and other accounts that have no value to anyone but the victim.

In this guide, I walk you through what you can and should do to protect yourself as much as possible from losing any accounts to hackers.

Use unique, strong passwords

Firstly, what should have been drilled into every internet user’s head by now: You really need to avoid having the same password on more than one account. For accounts you honestly don’t care about, it may not matter much, but all the accounts you’d hate to lose control of you should simply have a unique password. Bottom line.

As well as being unique, it’s important that the password is strong enough that it can’t be easily guessed. There are different schools of thought on this. Some think that a few random words are easier to memorize if needed, and easier to type in. Others prefer a random string of characters and numbers. If you ever need to enter your password manually and not via a password manager (see below), I recommend the word model.

Strong passwords aren’t just about keeping people out of your account. Almost as important is that hackers who come across a company’s user database normally have to crack (guess) each account’s password, as these are not stored in plain text but as so-called hash codes.

Foundry

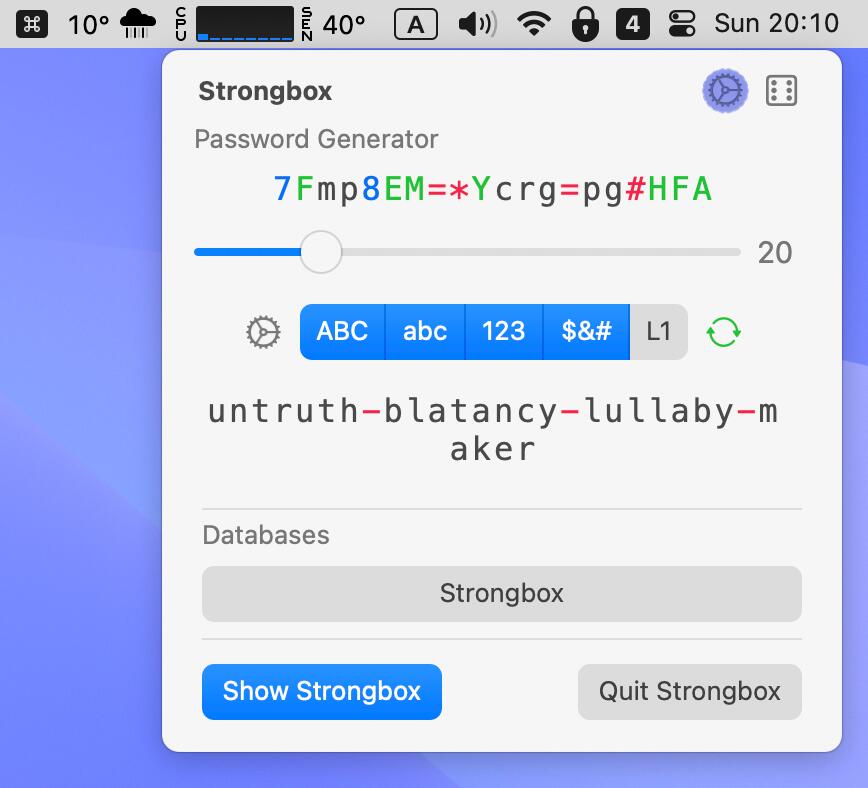

A password manager is a big help

To keep track of so many accounts, each with a unique password, most people need help, and the best help is a password manager. There are many to choose from, but what they have in common is that they are more convenient and more secure than letting your browser save your passwords.

All good password managers have a few things in common. They store all data encrypted and handle all the encryption and decryption on your devices so that the developer — or a hacker who has broken into the developer — can never see any passwords. They can generate new strong passwords and automatically save them. They automatically fill in the data, but only on the right website. And finally, they can synchronize passwords between different devices, so you can easily log in to your accounts no matter which device you use.

Another handy feature of some password managers is the ability to store things other than passwords — passports, bank account and debit card details, secure notes, and anything else you want to keep organized and don’t want outsiders to snoop on.

Two-factor authentication and two-step verification

Strong passwords protect against some threats, but not all. For example, malware that monitors everything you type on your keyboard can read passwords. Phishing websites can trick you into filling in usernames and passwords, and it doesn’t take many seconds for scammers to log in and change passwords.

It’s against this kind of threat that two-factor authentication and two-step verification protect you. Two-factor authentication means that to log in, you need two different types of proof. One is usually something you know (a password), the other can either be something you have — such as a hardware key or your mobile phone — or something unique to your physical person, i.e. biometric authentication such as fingerprints.

Two-step verification means that after filling in a password, you also have to fill in a code that is sent to your mobile phone number, for example by text message or email.

A common solution is the use of so-called “totp codes,” time-bound codes that can be used with specific apps (such as Google Authenticator) or in password managers. Since you must have physical access to the computer or mobile phone where the code generator is stored, this is a form of two-factor authentication. In addition, the device usually has a password or biometric unlock, and password managers always have a master password.

My recommendation for most users who are not particularly vulnerable through work or non-profit activities is to use the password manager to both store the login details and generate totp codes. It’s not as secure in absolute terms as having a separate app for the totp codes, but as long as you’ve chosen one of the better password managers, the risks are very small.

What you get in exchange for the slightly higher risk is a much simpler workflow when logging into different accounts, as the password manager usually automatically copies the totp code to the clipboard when it fills in the password and all you have to do is paste the code in the next step. This, in turn, means that it doesn’t hurt to enable two-factor authentication on as many accounts as possible, instead of only doing it on the most important ones, with the result that your overall security is much higher.

Keep track of hacked sites and leaked credentials

Whether you only started using the internet extensively in the 2010s or you’ve been hanging out online since the early days, you’ll probably have the occasional account that’s a few years old.

These accounts, especially if they’re accounts you don’t log into very often, may have been leaked when the provider was hacked at some point, without your knowledge. Most companies force all users to change their passwords after a breach, regardless of whether the hackers actually obtained the passwords, but if you don’t log in, you may not get a warning about it.

As well as the risk that someone may have gotten into that particular account, for example if you used a weak password (which was easy to do long ago before password managers were commonplace), leaks like this mean that the email address you used ends up on lists that various criminals can use to send out mass phishing or other attacks.

On the Have I Been Pwned website, you can enter your email address and quickly find out if it’s included in any of the databases of account details that have been leaked following various hacks. The site lists all the leaks your address is included in, and the date of the hack. You can then check these sites to see if you can still log in and if you need to change your password.

Some password managers have features to automatically keep track of hacked sites, for example through partnerships with Have I Been Pwned. The program can see when you created the account and when you last changed your password, and displays a warning if you haven’t changed your password since before the site in question was hacked.

Security questions, the right way

In the past, before two-factor authentication became commonplace, many sites used security questions that you had to answer to get into your account if you forgot your password, for example, or to change your password or email address. This is less common today, but still happens. The questions are often along the lines of “what city were you born in”? and “what was the name of your first pet?”.

The trick with such questions is not to answer honestly. Totally fictitious information cannot be guessed at and no hacker can find out by, for example, snooping around on Facebook or in some old blog you wrote a long time ago. If you have a password manager — which I highly recommend — you can create a secure note where you write down all the questions and answers.

If it’s a company that you might be in contact with by phone, it makes sense to choose answers that are easy to pronounce and/or spell and in the language of the company’s customer service team.

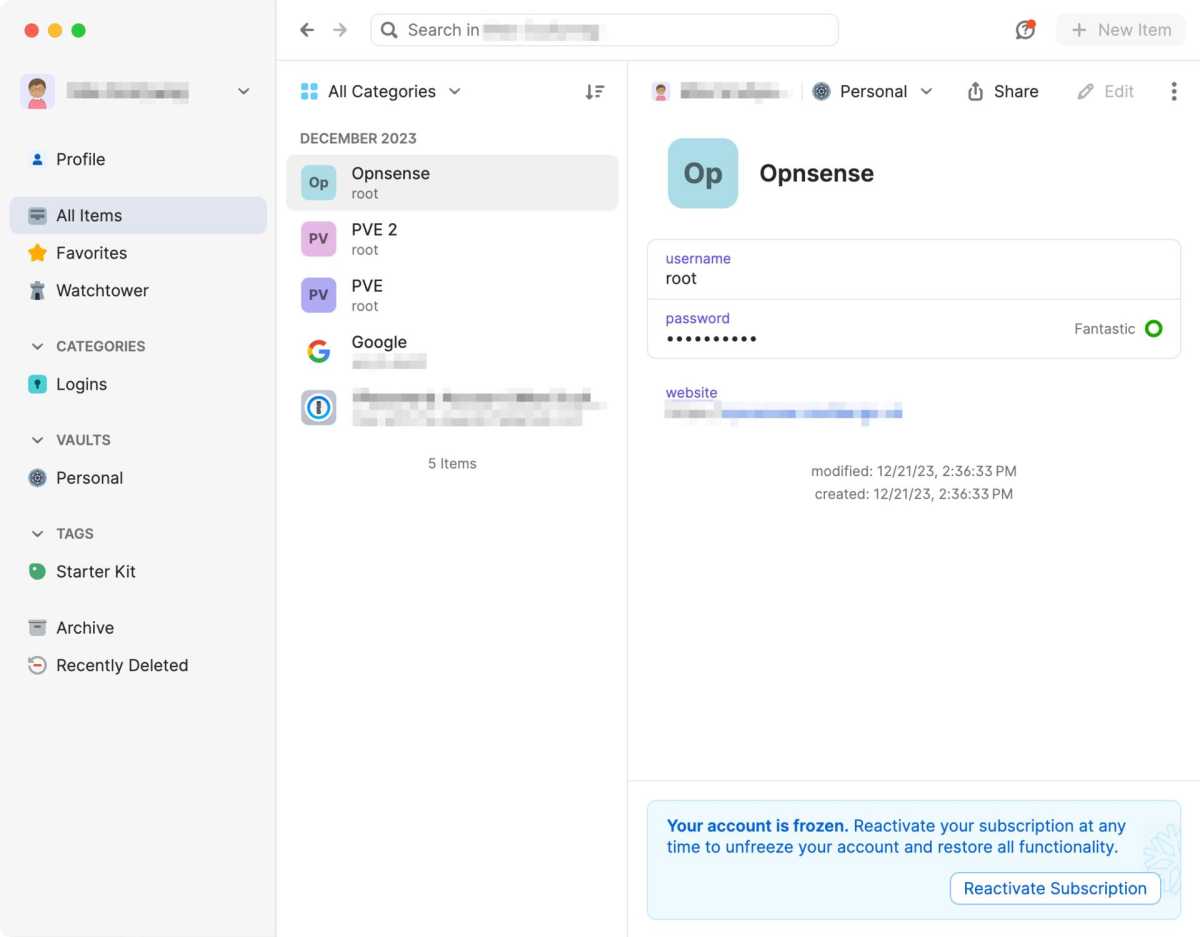

Log in with Google/Apple/Facebook

Nowadays, it has become common for sites not to require you to create a new account with an email address and password, but to offer you to log in via an account with someone else. The most common are Google and Facebook, but Microsoft, Apple, Github and various other sites also exist.

As long as the account with the larger company is really secure with a strong, unique password and two-factor authentication, this can reduce the risk of the smaller company’s account being hacked. If you don’t like password managers, this makes a lot of sense as it greatly reduces the number of passwords you need to memorize or write down on paper.

The first time you log in this way, the website creates an account for you, and you must agree to share certain information from the account with the other company. For example, Google shares your name, your email address, and your profile picture (if you have one).

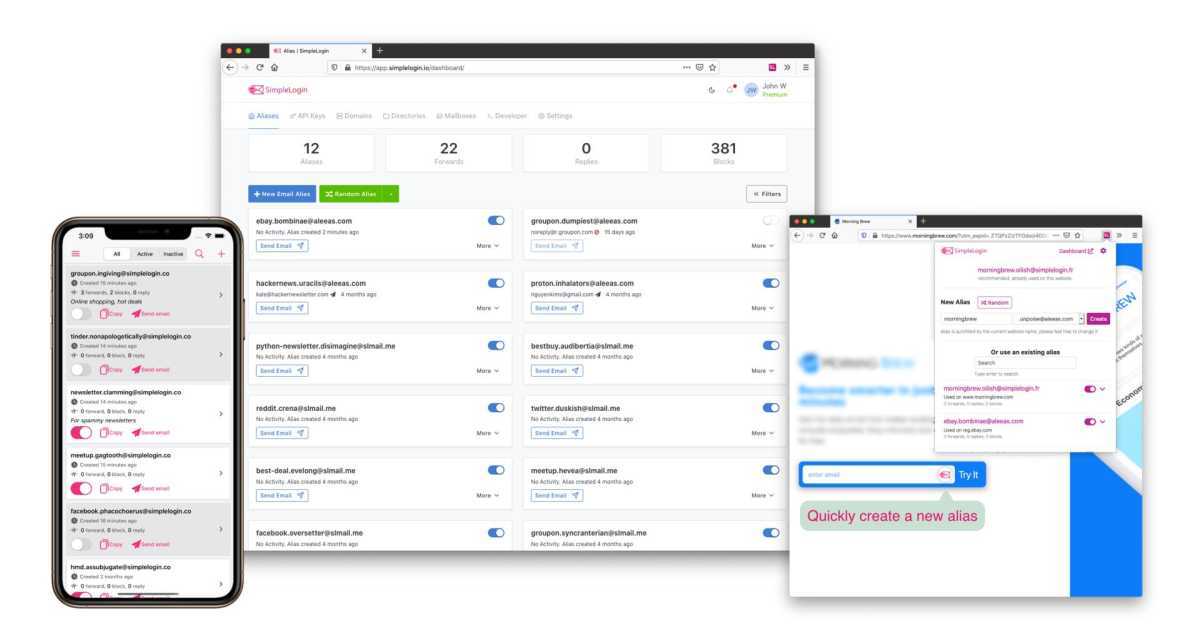

Simple Login

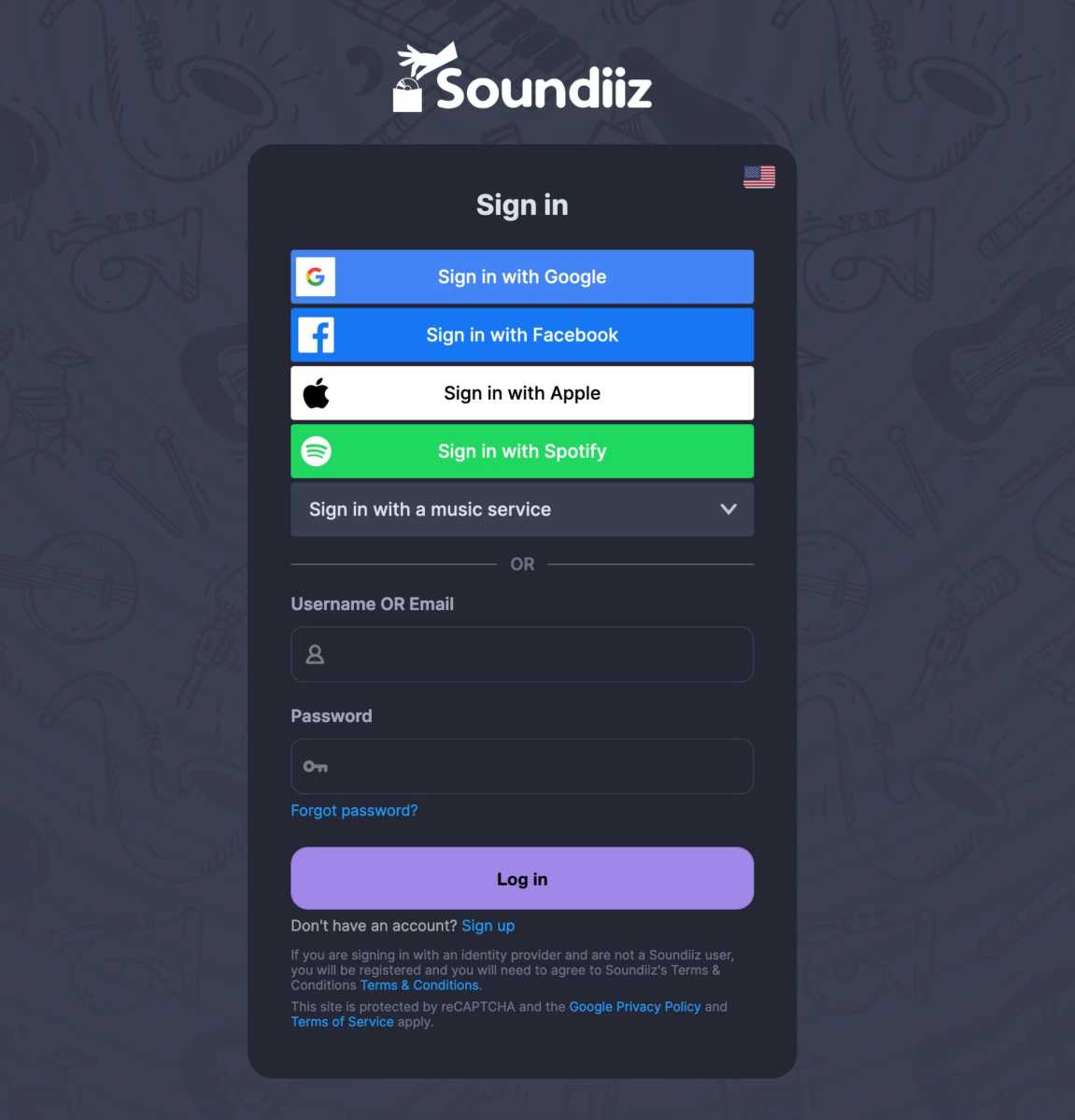

Unique email addresses for login

Because email addresses are so often used as usernames and so often leaked when companies are hacked, your email address is a security risk. Hackers can only try to get into your accounts if they know your username, and if you’re like most people, you use the same email address as your username on many or all of your accounts.

In recent years, services have emerged that try to remedy this. Some email services have a feature to create aliases, i.e. alternative addresses that also lead to you, but this quickly becomes cumbersome and most only have a limited number. Apple has unlimited numbers for iCloud Plus subscribers. The password managers 1Password and Proton Pass have built-in features that automatically create aliases for new accounts. The SimpleLogin service also provides unlimited aliases and the ability to use your own domain names for $30 a year.

Regain control of hijacked accounts

All the major tech giants have developed processes to help users regain access to accounts. Search for the company or service name and “account recovery.” Do this on a device that you are absolutely sure is not hacked or affected by malware, such as a friend’s computer or an old computer you have wiped and reinstalled the system on.

The level of difficulty varies and depends partly on how much trouble the hacker has caused. For example, a really thorough hacker can change both your email address and phone number. In some cases, and with some companies, you can hit the wall and have to settle for losing your account. Others have protections against that too. Facebook, for example, sends a special recovery link to the old email address if someone changes their address.

Once in, change your password and make sure you have the correct email address and phone number. Reset any two-factor authentication and set it up again, or set it up if you didn’t have it before. Some services have a feature to log out of all the devices you are logged in to — use it!

Keys are the future

A new technology that has started to roll out thanks to the full support of both Apple and Google is passkeys. It involves using asymmetric encryption in a clever way that makes it impossible for hackers to get into your accounts without access to your devices and passwords or biometrics to unlock them. Keys also protect against post-hack leaks, as the data stored on the server is meaningless without access to your devices.